Korngleng Sear 1,*

1 English Department, Spring Education Center, Phnom Penh, Cambodia

* korngleng@gmail.com

Received: 16 October 2023 Revised: 26 December 2023 Accepted: 23 February 2024

Cambodian Journal of Educational Research (2024)

Online First

Pages: 00–00

DOI: wil be added soon

Abstract

Since the 1980s, there has been a shift in attention from management to leadership because the latter is believed to help people thrive in the fast-changing world. Nowadays, leadership is a hot-button topic that has become a buzzword. People talk about it almost everywhere, from family to institutional and national contexts. This article aims to discuss issues concerning leadership, with a focus on leadership myths and essential skills for becoming a good leader. The article begins with the definitions of leadership, drawing on ideas from several leadership experts. It then discusses three common leadership myths related to the position or title of a leader, the functions of leadership and management, and leader-follower interactions. The article then outlines five essential leadership skills for becoming a good leader, focusing on ceaseless learning, openness, confidence, humility, and will. Finally, the article concludes by calling for every leader to make a difference in his or her community in order to make the world a better place.

Keywords: Leadership; management; good leaders, leadership myths; leadership skills

Introduction

Prior to the 1980s, people focused on management because it helped many organizations to thrive and reach their greatest achievements. During that period, Peter F. Drucker was named the father of modern management (Ben-Shahar, 2021). His management philosophies were adopted and practiced by many companies, such as Ford, General Electric, and Motorola (Drucker & Maciariello, 2004). Many leaders from non-profit and for-profit organizations flocked to ask for his advice (Ben-Shahar, 2021). At the end of the 1980s, people shifted their attention from management to leadership because they could see how powerful and effective leadership was when they implemented it properly (Maxwell, 2019). Since then, leadership has been woven into the fabric of many organizations across the globe, particularly in the business world.

The real power of leadership is all about people (Maxwell, 2017). However, many people desire to be leaders because they realize that they can take advantage of their positions. They want an elegant office, high salary, endless power, prestigious status, and countless perks (Maxwell, 2019). Those who possess this mindset are often headed for trouble in their leadership because their primary goals are to seek power and climb the organization ladder as high as possible. Sometimes, they do not care about the process and even step on others in order to fulfill their personal glory. When author and leadership expert John C. Maxwell spoke at an event, a host told him that, “Probably more than half of those people killed someone to obtain their current position or power” (Maxwell, 2022, p. 56). Author and pastor Han Finzel made a profound observation and argued that there are four leadership axioms:

- If you do what comes naturally, you will be a poor leader.

- People are confused about how to be a great leader because of poor role models. In other words, we lead as we were led.

- There seem to be more bad leaders than good leaders.

- The world needs more great leaders (Finzel, 2017, pp. 16-17).

These axioms are really useful. When I reflected on my observation and experience, I could see that some leaders with whom I have worked fall into these categories of leaders. My interactions with my friends and colleagues have also proved that these axioms are practical in determining the quality of leaders whether they are good or bad.

According to data from Gallup (Kim & Mauborgne, 2017a), only 50% of the employees surveyed associated themselves with the work, while 20% purposefully disengaged themselves from their tasks. The 20% group alone could influence the US economy by approximately half a trillion dollars each year. According to the same source, the root cause of this comes from poor leadership. Another survey showed that 67% of employees across the globe had no engagement with their work, and 18% were actively disengaged (Hunsaker & Hunsaker, 2022).

Maxwell (2008) once argued that people take a job for some reason. Perhaps they want to be a part of something special and significant. They may also want to contribute to building a great organization. They may find the visions of the company resonate with them. They want to climb the company’s career ladder, or the company offers them a good salary. However, the main reason people decide to leave their jobs is often linked to other people or leaders in the workplace. Bad leaders drive people, competent or incompetent, out of the company. As Maxwell (2011) rightly put it, “People quit people, not companies” (p. 58). In light of this, it can be argued that leadership, if not implemented properly, will result in a tragedy for humans. Therefore, we must treat leadership seriously and grow ourselves to become leaders who positively rather than negatively impact the world.

This article aims to discuss common leadership myths and essential skills for becoming a good leader. It begins by explaining what leadership is. It then elaborates on three common leadership myths. After that, the article discusses some essential leadership skills that every leader should embrace to become a good leader who can positively influence people, the community, and the world. The article concludes that leadership is so powerful that it can tremendously change people’s lives and move the world. Thus, those who are in leadership positions should use their power carefully to bring maximum advantages to people and the world.

Definitions of leadership

At present, leadership is a buzzword. People talk about it almost everywhere. John C. Maxwell remarked that leadership is an inexhaustible subject (Maxwell, 2011). Therefore, how do we define leadership? Author Jim Collins asserted that leadership exists when people are free to follow and not to follow (Collins & Lazier, 2020). Likewise, professor and author Brené Brown defined a leader as a person who seeks the potential in people and is brave enough to develop that potential (Brown, 2018). Similarly, author and educator Stephen R. Covey believed that leadership is seeing the worth and potential in people and letting them realize their potential (Covey, 2013). However, Hans Finzel and John C. Maxwell argued that leadership is about influencing people (Finzel, 2017; Maxwell, 2022). For motivational speaker Brian Tracy, he noted that leadership is the capacity to motivate people to work for us because they want to (Tracy, 2010). As for Kouzes et al. (2018), they argued that:

Leadership is not a formal position or an official place in the organizational hierarchy. Leadership is not a genetic trait or limited by gender, ethnic or racial background, family or social status, appearance, or nationality. Leadership is an observable and learnable set of skills and abilities that is accessible to everyone. (p. 2).

If someone asks me to define what leadership is, my answer would focus on making a difference in people’s lives. Based on these definitions, it is evident that leaders have followers who are willing to comply with their orders or commands, and good leaders always see the seed of greatness in other people and help them unlock and reach their potential. Leaders appear in all sizes, shapes, genders, races, ages, and backgrounds, but the one thing leaders, good or bad, have in common is influence (Finzel, 2017; Maxwell, 2018, 2022). Leadership is learnable (Maxwell, 2022), and everyone can become a leader as long as he or she can influence other people (Maxwell, 2018). If we have an unstoppable desire to become leaders, we have to learn to increase our influence on a daily basis.

Three common myths of leadership

Because leadership is a hot-button topic, people from every walk of life often discuss it privately or publicly. A great deal of leadership books have been published and sold on the market, and experts such as John C. Maxwell, Brian Tracy, and Robin Sharma have conducted countless workshops on the topic of leadership. However, the concept of leadership can cause confusion, as there are at least three myths about it.

Myth 1: Leadership is not about a position or title

In the last few decades, leadership experts have often argued that leadership is not about position. Specifically, leadership is not about a position, power, or title (Maxwell, 2020; Sharma, 2019). This statement might be right in some contexts and cultures but incorrect in others, particularly in developing countries. In fact, a position or title is one part of leadership. Why is it like that?

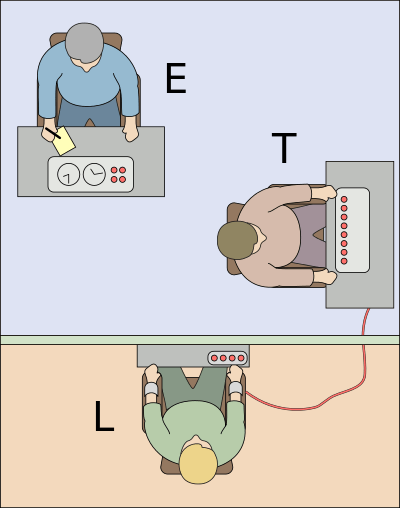

First, a position helps a leader increase his or her influence.Figure 1 below is a renowned experiment by Professor Stanley Milgram of Yale University. The experiment aimed to know how much ordinary people, knowing that their actions could harm an innocent person, would be willing to do so under the orders of an authority figure (Cialdini, 2021). In the experiment, the letter E represented the experimenter, T represented the teacher or the subject, and L represented the student as an actor. The experimenter and the teacher sat in the same room, but the student sat in another room. The teacher and the student could communicate but could not see each other. First, the volunteers were invited to be the teachers in the experiment room and told that each time the student made a mistake, they had to shock the student as a punishment. The shock increased by 15 volts every time a student answered incorrectly. Surprisingly, two-thirds of the 40 teachers, hearing that the student suffered terribly from the shock, still followed the experimenter’s order to continue the shock until 450 volts, which could make the students paralyzed.

Figure 1. The Milgram experiment (“Milgram experiment,” 2023)

Based on the Milgram experiment, we could see why soldiers in World War 2, knowing that their actions could kill millions of people, still followed Adolf Hitler’s orders. In the Cambodian case, soldiers, even realizing that many Cambodian people, families, and children would suffer from their actions, still followed Pol Pot’s orders. Authority or position definitely increases a leader’s influence on people.

Second, a position allows a leader to get involved in making decisions. The Pareto Principle states that 20 percent of the people make 80 percent of the decisions (Maxwell, 2018). The question is who the top 20 percent of the people in an organization are. It is obvious that only people, such as executives and leaders at the executive level, can contribute to making decisions that result in the successes and failures of an organization.

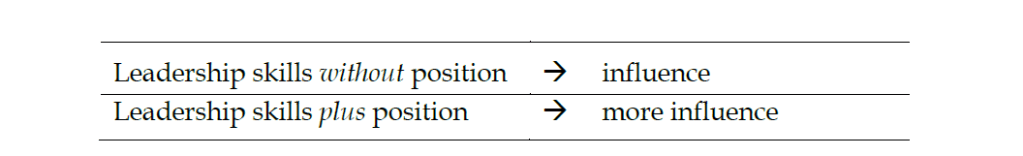

Third, a position can exaggerate a leader’s reality. If we put two people together (for example, one is a high-ranking person, and the other is an ordinary person), who tends to have a higher influence on us? It is likely that a person with a position or power will influence us. We tend to think that he or she is more skillful, knowledgeable, competent, and intelligent than the other. The halo effect is the answer to this bias. The halo effect takes place when a single positive characteristic of an individual shapes how he or she is perceived in other areas (Cialdini, 2021). When we meet a leader from a large company, we are likely to be affected by the halo effect. The influence of a position is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. The influence of a position

Although a position is part of leadership, relying heavily on it tends to lead to a huge mistake (Finzel, 1994). Ineffective leaders use a position to move employees in their desired direction. Good leaders would rather use such skills as relationship, communication, motivation, and empowerment than their position to increase their sphere of influence.

Myth 2: Leadership is more powerful than management and vice versa

Some people confusingly believe that leadership is more powerful than management in growing an organization. As Maxwell (2020, p. xv) noted, “Everything rises and falls on leadership.” He said that because he is a leadership expert. However, if we are management scholars, we will believe that management is more effective in practice than leadership, and we might argue that everything rises and falls based on management. Moreover, many people regard leadership as a near-synonym for management (Kotter & Rathgeber, 2016; Maxwell, 2022).

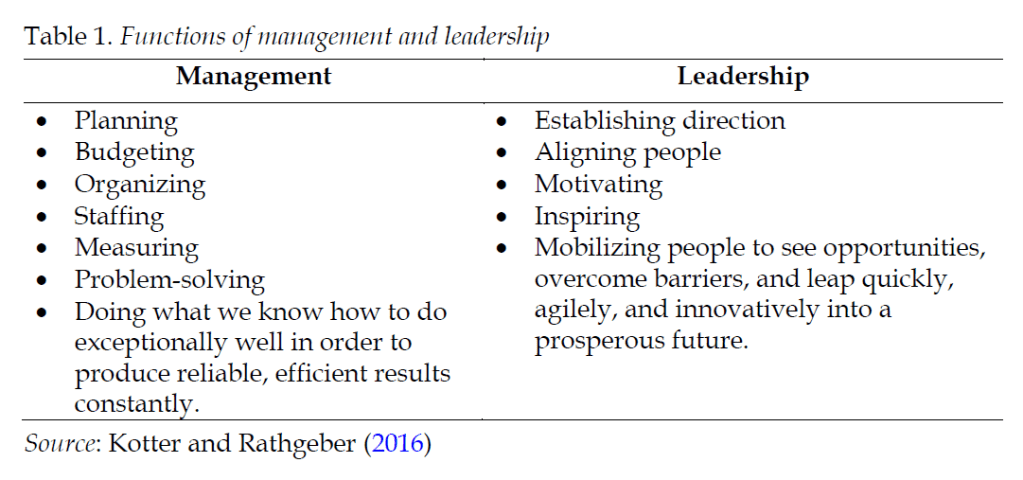

In fact, leadership and management are vastly different subjects, and they are used for distinct purposes (Kotter & Rathgeber, 2016). Leadership is about influencing people and creating a positive change, whereas management is used to maintain processes and systems (Maxwell, 2022). Furthermore, the roles of a manager are planning, organising, executing, and controlling, but a leader’s roles are making change, thinking in the long term, casting vision, building relationships, and extending networks with other people (Ruan et al., 2024). According to Harvard Business Review (2017), management is about controlling systems, predicting the future, responding to complexity, and organizing processes to sustain results. Conversely, leadership is about responding to change, producing results, and seeing untapped opportunities in turmoil situations.

Source: Kotter and Rathgeber (2016)

As shown in Table 1, management and leadership are different due to their functions and objectives. When a person plans in the short or long term, calculates finances for a project, and solves small or big problems, he or she is implementing management. Nonetheless, practicing leadership is about directing people, enabling team members to be on the same page to achieve goals, and motivating people to give their best for the organization (Kotter & Rathgeber, 2016).

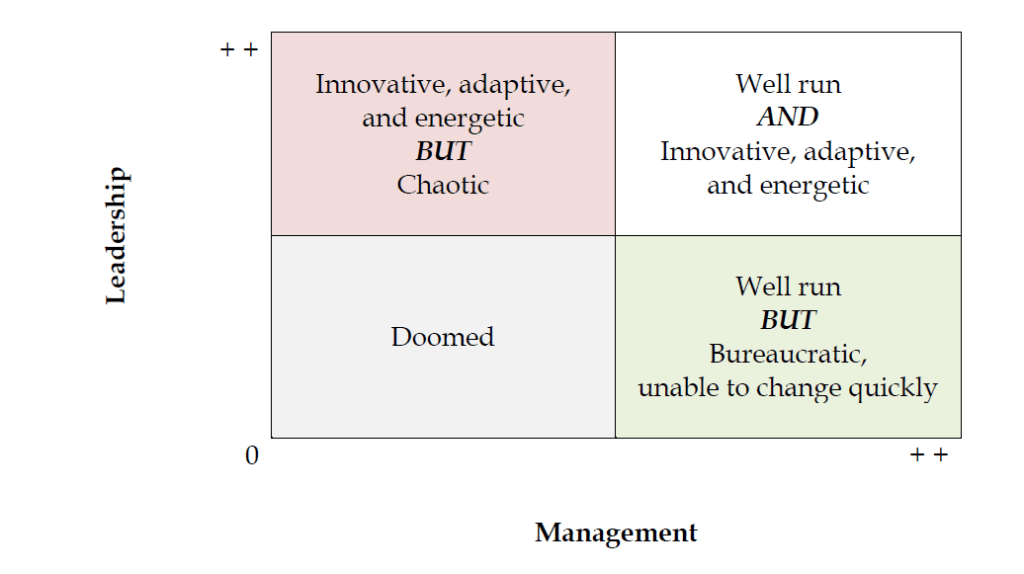

Leadership and management are inextricably linked and parts of the fabric of organizations. Every company must meticulously embrace both management and leadership if it desires to increase productivity and maximize success. Lacking the two or one of them will put a company on the brink of failure and become irrelevant. Figure 3, taken from Kotter and Rathgeber (2016), illustrates this point well. First, when an organization places no value on management and leadership, it will be doomed. Second, if a company implements leadership without management, employees are innovative, adaptive, and energetic, but it can cause chaos in the workplace. Third, although practicing management in the absence of leadership could run an organization smoothly, it creates bureaucracy and makes it impossible for people to adapt quickly due to external changes or turbulence. Fourth, overriding focus on one over the other will destabilize the effectiveness and efficiency of an organization. In short, an organization’s growth and sustainable results are fueled by fully adhering to a blend of management and leadership at a highly equal degree (Kotter & Rathgeber, 2016).

Figure 3. Organizations must adopt both management and leadership for effectiveness

Myth 3: A position makes a leader lonely at the top

When I was a university student, a lecturer who taught a leadership subject told a story of his daughter. He said that she was clever and cunning. She was a class monitor in high school. When she became an employee in a company, her ability lifted her to the top position in the organization quickly. He ended the story by saying that the higher a leader’s position, the lonelier he or she becomes.

As I have immensely associated myself with a personal growth plan and considered leadership to be my number one growth area, I later learned that the position does not make a leader lonely at the top. It is a person who wants to make it that way (Maxwell, 2011). Suppose that we are leaders in an organization and work 10 hours a day. If we sit in our office most of the time, then we will be lonely at the top. Conversely, if we balance between task-oriented and people-oriented and go out to interact with people, then we are not the king of the hill alone.

Leaders proceed to stay on the top alone because they feel insecure with people. They are threatened and intimated by potential employees who are climbing the corporate ladder. As a result of their boundary building, people feel demotivated, lose opportunities to grow, and leave the organization to find a new place to shine. Leadership is not about separating or setting ourselves apart from people. It is all about staying with and standing by people or engaging in different activities with them (Imai, 2021).

Five essential skills for becoming a good leader

There are many essential skills for becoming a good leader. According to leadership experts, five essential skills are worth considering when discussing skills that make a person become a good leader. They include ceaseless learning, openness, confidence, humility, and will (Collins, 2001; Grant, 2021).

Ceaseless learning

Years ago, leadership experts Warren Bennis and Burt Nanus conducted a research study and discovered that leaders were different from their followers due to their ability to continuously learn and improve their skills (Maxwell, 2022). In the fast-paced, changing world with cutting-edge technology, leaders must improve themselves relentlessly and make a decision to be lifelong learners if they wish to stay relevant. As the father of modern management, Peter Drucker wrote, “The only skill that will be important in the twenty-first century will be the skill of learning new skills. All else will eventually become obsolete” (Tracy & Chee, 2013, p. 76). The good news is that leadership is learnable, and leaders who learn the most can outperform their competitors. Even in the face of failure, lifelong learning leaders would never waver, and no setbacks can hold them back because their knowledge and expertise empower them to overcome adversities, solve problems, break out of barriers, and keep them from falling off track. As philosopher Francis Bacon said, “Knowledge is power” (Maxwell, 2022, p. 18).

It is worthwhile to note that knowledge, wisdom, and insights never come to leaders by accident. Leaders must be on the lookout for them, and good leaders understand that learning is a never-ending quest. For example, author Norman Vincent Peale often reminded himself that when he stopped learning, he would die. As a result, he kept learning until his last breath (Blanchard, 2018). Philosopher Goethe said, “Never let a day pass without looking at some perfect work of art, hearing, some great piece of music and reading, in part, some great book” (Maxwell, 2021, p. 112). A day without learning new things is unacceptable to good leaders. They actively read books, ask questions, reflect on their learning, and apply new ideas in their personal and professional lives. Good leaders still want to know how to improve themselves.

Openness

Throughout my observation, I believe there is a correlation between learning and openness. A lifelong learner is an open-minded person. Consider the 16th president of the United States, Abraham Lincoln. He was an avid reader and an open person; as a result, American citizens submitted the most suggestion letters during his tenure. Good leaders ask people for ideas, listen to them carefully, and take those opinions into consideration. In doing so, it makes people feel valuable and respected. If we proceed to become open-minded leaders whom people want to approach, the following four points may be useful.

Lead with questions: Many leaders like giving orders, but open-minded leaders adhere to the Socratic method. They query questions because they know that great insights and ideas come from the right questions with the right people. Collins (2001) found that top company leaders led their people with questions to gain understanding. Their common questions include: “So, what’s on your mind?” “Can you tell me about that?” “Can you help understand?” and “What should we be worried about?” (Collins, 2001, p. 75).

Lead with active and passive listening: To motivate people to keep answering questions, leaders must actively and passively listen to them. Good leaders are good listeners (Carnegie, 2020; Finzel, 2017). They listen to seek understanding first before they start leading people. According to Berger (2020), active listeners possess five tactics. First, active listeners use minimal encouragers. They use body language such as nodding heads, looking at the speaker’s eyes, and leaning forward. They also use verbal responses like “Yes,” “Uh-huh,” or “Okay, I see.” Second, active listeners ask open-ended questions like “Can you tell me more about that?” or “Wow, how did that happen?” Third, active listeners harness effective pauses. Pausing means silence, and silence makes people uncomfortable. Therefore, it inspires people to fill up the conversational space. Hostage negotiators often use this technique with suspects. They would rather pause than ask follow-up questions to get answers from suspects. Fourth, active listeners reflect on what they hear. They repeat or restate the speaker’s words to show they are engaging. Finally, active listeners label emotions. They use their hearts to understand the speaker’s emotions.

In addition to leading with active listening, good leaders are also good passive listeners. Effectively passive listening requires using our ears coupled with our eyes, heart, and undivided attention. The traditional Chinese character below gives an illustration of this point.

This character is pronounced “Tīng,” which means “listen” in English. It comes from the combination of the words:

耳: Ears

目: Eyes

心: Heart

一: Undivided attention (Covey, 2006)

Thus, to become good passive listeners, we must use our ears to listen to the speaker’s words, our eyes to look at the speaker’s body language, our hearts to understand the speaker’s mind, and our undivided attention to focus on the speaker.

Lead with psychological safety: According to Edmonson (2019), psychological safety is a belief that there are no formal and informal punishments when people ask for help and admit their mistakes or failures. Psychological safety exists when people in the workplace can speak up, share ideas, and ask questions without fear of being blamed or embarrassed. Edmonson (2019) found that teams with psychological safety tended to report more errors but made fewer errors than those working in psychologically unsafe environments. Psychologically safe teams were more likely to feel free to express their ideas, ask questions, and report mistakes without reprimand. This allowed them to learn from their failures and make fewer and fewer errors. Psychologically unsafe teams, however, were afraid of blame and penalties, making them avoid admitting their mistakes and telling the truth. As a result, they often continue repeating the same mistakes (Grant, 2021).

Lead with a fair process: According to Kim and Mauborgne (2015), when leaders lead with a fair process, it communicates intellectual and emotional recognition to people. It shows that they are treated as human beings rather than labor or personnel. To create a culture of a fair process, three elements, such as engagement, explanation, and expectation, are needed.

- Engagement is involving people in making decisions by asking for their ideas. It allows leaders to show respect to people and value their opinions. Engagement helps leaders carefully weigh all the ideas and select the best one from all comments.

- Explanation means showing people the rationales why leaders accept one idea and reject others. Explanation convinces employees to have confidence in leaders’ intentions, although their recommendations have been turned down.

- Expectation means clarifying the new rules or policies of the game when a new idea is confirmed and implemented in the organization. Leaders can inform people of the standards and demands from them. What are the goals to achieve? Who bears responsibility for what? What are the consequences if employees fail to reach the requirements?

In essence, we must implement these four points intentionally to ensure openness. As human beings, we often prefer ordering rather than asking, talking instead of listening, responding negatively to others’ mistakes instead of empathizing, and being biased instead of being fair. It takes a leader with rock-solid character, emotional strength, and a good attitude to practice these points well.

Confidence

Confidence plays a key role in public speaking. It is difficult to deliver an intriguing speech without confidence, and it is more difficult to convince others if we are not confident with our speech. Who are the great orators in our minds? Is it John F. Kennedy, Winston Churchill, or Barack Obama? I do not know the answer, but I believe that Donald Trump is probably not the first name in our minds. While Winston Churchill and Abraham Lincoln were famous for their clear explanation, logical argumentation, critical thinking, and reasonable ideas (Berger, 2016), Trump’s speech had none of these. Here is his speech during one of his presidential campaigns:

I would build a great wall, and nobody builds walls better than me, believe me, and I’ll build them very inexpensively. Our country is in serious trouble. We don’t have victories anymore. We used to have victories, but we don’t have them. When was the last time anybody saw us beating, let’s say, China, in a trade deal? I beat China all the time. All the time (Berger, 2023, n.p.).

Undoubtedly, people criticized Trump’s speech. Time Magazine called it “empty” (Berger, 2023, n.p.). However, those who mistook his speech as empty or meaningless found themselves terribly beaten at the end. Trump is an excellent salesman. He is persuasive and good at motivating people. He has been confident and powerful in his public speaking. Less than one year after Time Magazine mocked him, Trump was elected the 45th president of the United States (Berger, 2023). To improve our confidence, the following strategies should be considered.

Improving our competence. No doubt, there is a firm correlation between competence and confidence (Grant, 2021). If our competence scores a 5 out of 10, then our confidence operates at the same point. To increase our confidence, we must improve our competence. When we move up our competence from a 5 to a 9, so will our confidence. According to Harvard Business School professor Linda Hill and executive coach Kent Lineback, competence refers to operational, technical, and political knowledge (Harvard Business Review, 2017).

Connecting with confident people. It is evident that when we connect with a confident person, we tend to be as confident as him or her. As Maxwell (1989) noted, connecting with confident people could help increase our confidence. For example, a few years ago, I had a chance to deliver a sharing session to a group of teachers at my workplace. As a shy introvert, I have struggled with my public speaking for years. I believed the ideas shared in the presentation would help the attendees learn and grow, but I did not believe in myself. My solution was to ask my confident manager to sit nearby me. Her presence precisely helped maximize my confidence. I explained my concepts one by one until the end of the presentation. It turned out to be a pleasant and unforgettable experience in my life.

Breaking down challenges into small parts. Nobel Prize winner Albert Einstein explained that if we break down any challenges into manageable components and tackle them individually, even the biggest ones will be solved successfully (Kim & Mauborgne, 2017b). The process of solving small challenges one after another to achieve a major goal will remarkably improve people’s confidence from the beginning to the end of any task.

Mastering a task helps enhance our confidence, leading to better performance. Our performance near or before other people leads to two consequences: it increases or decreases the performance. For instance, if we exercise by running with other people, we will run faster, longer, and farther than solo running (Berger, 2016). When the task is easy and very familiar to a person as he or she has done it hundreds or thousands of times, it will increase his or her performance. However, when it comes to a difficult and complex task unfamiliar to a person, or he or she has only done it a few times, then it will decrease his or her performance. For example, if we place a schoolteacher to play football in a stadium full of spectators, he or she will not perform well, and it even decreases his or her performance compared to playing football alone. According to Stanford professor Bob Zajonc who conducted an experiment with cockroaches (Berger, 2016), a person’s performance will decrease in front of an audience when he or she is not specialized in his or her task, or when he or she has merely done that task a few times. In contrast, a person’s performance will increase when he or she can master the task. This means that our confidence increases due to our expertise in the task. Thus, mastering a task is equated to increasing our confidence, resulting in better performance.

Humility

Good leaders are confident in their abilities, but they are also humble. Indeed, at the center between overconfidence (confidence exceeding competence) and underconfidence (not believing in one’s own ability) lies another quality called confident humility. Confident humility occurs when people believe in their capability and simultaneously appreciate that they do not have answers to every question and solutions to every problem (Grant, 2021). People desire to follow confident leaders who energize them, but good leaders embrace the yin and yang of Taoist philosophy (Collins & Lazier, 2020). They are confident and humble (Grant, 2021). To become humble leaders, we should consider the following three ideas.

Possess a teachable attitude: People often possess one of the following three attitudes regarding learning. First, learning from nobody (an arrogant attitude). Second, learning from only one person (a naïve attitude). Third, learning from everyone (a teachable attitude) (Maxwell, 2012). Good leaders have a thirst for knowledge and learn new things from everyone. They are willing to learn, unlearn, and relearn. They realize that the quest for knowledge never reaches the finish line (Grant, 2021). Leonardo da Vinci was known as a “universal man” because of his sharp ability to become an expert in diverse fields. He was a painter, engineer, scientist, sculptor, architect, and theorist. His teachable attitude separated him from the rest, as we can find in his renowned notebook. He used it to record knowledge whenever he learned something new (Maxwell, 2007).

Consider ourselves beginners rather than experts: Prideful leaders are self-centered. They are egoists. They possess a mindset that if they cannot do anything, neither can others. Sadly, their ego prevents them from improving. As American journalist Sydney Harris said, “A winner knows how much he still has to learn, even when he is considered an expert by others; a loser wants to be considered an expert by others before he has learned enough to know how little he knows” (Maxwell, 2012, pp. 87-88)

Admit our weaknesses and mistakes: When I was a young employee, some of my managers advised me not to show my weaknesses, which were recognized as a downside in my profession. However, as I got older and became more mature, I learned that everyone has his or her own strengths and weaknesses. Psychologists found that when people admit their mistakes and acknowledge their wrongdoings, it does not make them look less competent in the eyes of others. Conversely, it indicates that they are honest and willing to learn new things (Grant, 2021).

Overall, good leaders believe in their abilities and are confident in their strengths. They are also modest in asking questions, admitting their weaknesses, and learning from everyone. Thus, adopting confident humility is the sweet spot for every leader.

Will

Stanford professor and author Jim Collins wrote and published seven books on business and leadership. His books answered the question of what makes a company tick. In his books, he often highlighted the leaders who are the real sparks behind their great companies. Noticeably, Collins brought out the lessons we could learn from those great leaders by looking back at their personal backgrounds and professional experiences. For example, in his 2001 book, Good to Great, Collins called the CEOs who made the transition of their companies from good to great Level 5 leaders. Those Level 5 leaders were all cut from the same clothes. They were quiet, self-effacing, reserved, gracious, mild-mannered, and even shy (Collins, 2001).

In their 2011 book, Great by Choice, Collins and Hansen called those CEOs 10 Xers (pronounced “ten-Ex-ers”). The 10 Xers were paranoid, contrarian, independent, obsessed, monomaniacal, exhausting, and weird (Collins & Hansen, 2011). No matter how their personalities were, where they came from, and what they did, they shared one common quality. It is their will or ambition to build great organizations and change the world (Collins, 2001; Collins & Hansen, 2011; Collins & Porras, 2005). For example, from 1975 to 1991, Gillette, a company producing safety razors and personal care products, was in turmoil, affecting the greatness of the company. However, its CEO, Colman Mockler, demonstrated his strong will to stay with the company. Instead of capitulating, Mockler chose to stand firmly to fight against the odds and build Gillette to become one of the greatest companies in the world (Collins, 2001). As Maxwell (2018) noted, great leaders think about the benefits for their companies first, their employees second, and themselves last. Thus, only leaders who possess a strong will are more likely to produce great outcomes (Collins, 2001; Collins & Porras, 2005).

Conclusion

Leadership is about influencing people, and good leaders always see the seed of greatness in people and help them reach their potential. The position of a leader is one part of leadership. It is not everything. Moreover, leadership and management are quite distinct, so companies need to embrace both to become highly successful. The position of a leader does not make him or her lonely, but it is the choice of leadership style of the leader that sets himself or herself apart from other people.

Good leaders are lifelong learners, and they learn to fuel growth, not to feed their ego (Maxwell, 2022). They are open to recommendations, ask for creative ideas, and meticulously consider those opinions. They show their confidence and competence to gain influence, and they tend to simultaneously confess their weaknesses and ask for help from people when needed. Furthermore, good leaders tend to simplify their lives. They rarely try to make themselves unreachable icons. They usually run businesses beyond profit, and they have a strong desire, will, and ambition to build great companies or make a difference in their community, society, or the world.

Thus, to become good leaders, we should set a life goal to grow ourselves. We should love, care, and respect our people because these three elements are the foundation of leadership. We should add value, serve, and develop our people because it is the heart of leadership. We should also put our organization, community, or society ahead of our personal glory because it is the highest place of leadership.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to express his gratitude to Dr. Kimkong Heng, the Editor-in-Chief of the Cambodian Journal of Educational Research, for his constructive feedback and multiple rounds of edits. The author would also like to thank Dr. Koemhong Sol, the Co-Editor-in-Chief of the Cambodian Journal of Educational Research, for his final edits. Finally, the author wishes to thank two anonymous reviewers for their comments on an earlier version of this article.

Conflict of interest

None.

The author

Korngleng Sear is an English as a Second Language (ESL) teacher at Spring Education Center. He is currently a research mentee in the research internship program of the Cambodian Education Forum. He has been a student of personal growth since 2018. His areas of interest are leadership, education, business, psychology, relationships, and social influence.

Email: korngleng@gmail.com

References

Ben-Shahar, T. (2021). Happier, no matter what: Cultivating hope, resilience, and purpose in hard times. The Experiment.

Berger, J. (2016). Invisible influence: The hidden forces that shape behavior. Simon & Schuster Paperbacks.

Berger, J. (2020). The catalyst: How to change anyone’s mind. Simon & Schuster Paperbacks.

Berger, J. (2023). Magic Words: What to say to get your way. Harper Business.

Blanchard, K. (2018). The heart of a leader: Insights on the art of influence. Jaico Publishing House.

Brown, B. (2018). Dare to lead: Brave work. Tough conversations. Whole hearts. Random House.

Carnegie, D. (2020). The leader in you. Diamond Pocket Books (P) Ltd.

Cialdini, R. B. (2021). Influence: The psychology of persuasion. Harper Business.

Collins, J. & Hansen, M. T. (2011). Great by choice: Uncertainty, chaos, and luck-why some thrive despite them all. Random House Business Book.

Collins, J. & Porras, J. I. (2005). Built to Last: Successful Habits of Visionary Companies. Random House Business Book.

Collins, J. (2001). Good to great: Why some companies make the leap and others don’t. Random House Business.

Collins, J. & Lazier, B. (2020). Beyond Entrepreneurship 2.0: Turning your business into an enduring great company. Portfolio / Penguin.

Covey, S. (2006). The 6 most important decisions you’ll ever make: A guide for teens. Touchstone.

Covey, S. R. (2013). The 7 habits of highly effective people: Powerful lessons in personal change. Simon & Schuster.

Drucker, P. F., & Maciariello, J. A. (2004). The daily Drucker: 366 days of insight and motivation for getting the right things done. Harper Business.

Edmonson, A. C. (2019). The fearless organization: Creating psychological safety in the workplace for learning, innovation, and growth. Wiley.

Finzel, H. (1994). The top ten mistakes leaders make. Victor.

Finzel, H. (2017). Top ten ways to be a great leader. Jaico Publishing House.

Grant, A. (2021). Think again: The power of knowing what you don’t know. Viking.

Harvard Business Review. (2017). Harvard business review manager’s handbook: The 17 skills leaders need to stand out. Harvard Business Review Press.

Hunsaker, P. L., & Hunsaker, J. (2022). Essential managers management handbook. DK.

Imai, M. (2021). Strategic KAIZEN™: Using flow, synchronization, and leveling [FSL™] assessment to measure and strengthen operational performance. McGraw Hill.

Kim, W. C. & Mauborgne, R. (2015). Blue ocean strategy: How to create uncontested market space and make the competition irrelevant. Harvard Business Review Press.

Kim, W. C. & Mauborgne, R. (2017a). The W. Chan Kim and Renée Mauborgne blue ocean strategy reader: The iconic articles by bestselling authors of blue ocean strategy. Harvard Business Review Press.

Kim, W. C. & Mauborgne, R. (2017b). Blue ocean shift: Beyond competing – proven steps to inspire confidence and seize new growth. Macmillan.

Kotter, J. & Rathgeber, H. (2016). That’s not how we do it here!: A story about how organizations rise and fall – and can rise again. Portfolio / Penguin.

Kouzes, J., Posner, B., & Calvert, D. (2018). Stop selling & start leading: How to make extraordinary sales happen. Wiley.

Maxwell, J. C. (1989). Be a people person: Effective leadership through effective relationships. Jaico Publishing House.

Maxwell, J. C. (2007). Talent is never enough: Discover the choices that will take you beyond your talent. Thomas Nelson.

Maxwell, J. C. (2008). Leadership gold: Lesson I learn from a lifetime of leading. Thomas Nelson.

Maxwell, J. C. (2011). The 5 levels of leadership: Proven steps to maximize your potential. Center Street.

Maxwell, J. C. (2012). The complete 101 collection: What every leader needs to know. HarperCollins Leadership.

Maxwell, J. C. (2017). The power of your leadership: Making a difference with others. Center Street.

Maxwell, J. C. (2018). Developing the leader within you 2.0. HarperCollins Leadership.

Maxwell, J. C. (2019). Leadershift: The 11 essential changes every leader must embrace. HarperCollins Leadership.

Maxwell, J. C. (2020). The leader’s greatest return: Attracting, developing, and multiplying leaders. HarperCollins Leadership.

Maxwell, J. C. (2021). The self-aware leader: Play to your strengths and unleash your team. HarperCollins Leadership.

Maxwell, J. C. (2022). The 21 irrefutable laws of leadership: Follow them and people will follow you. HarperCollins Leadership.

Milgram experiment. (2023, December 1). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Milgram_experiment&oldid=1185296552

Ruan, J., Cai, Y. & Stensaker, B. (2024). University managers or institutional leaders? An exploration of top-level leadership in Chinese universities. Higher Education, 87, 703–719. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-023-01031-x

Sharma, R. (2019). Leadership wisdom from the monk who sold his Ferrari. Jaico Publishing House.

Tracy, B. & Chee, P. (2013). 12 disciplines of leadership excellence: How leaders achieve sustainable high performance. McGraw Hill Education.

Tracy, B. (2010). How the best leaders lead: Proven secrets to getting the most out of yourself and others. Amacom.