Sophon Hieng, Sondom Thlang, and Seanghai Nget

Battambang Teacher Education College

Battambang, Cambodia

Cambodian Journal of Educational Research (2023)

Volume 3, Issue 1

Pages: 20-43

https://doi.org/10.62037/cjer.2023.03.01.02

Article history:

Received 26 July 2022; Revised 15 May; Accepted 31 May 2023

Abstract

The purpose of this research was to determine which teaching method was more effective in teaching English grammar. Using a matched control experimental design, 33 pairs of primary student teachers at Battambang Teacher Education College were equally assigned into two groups, the control and experimental groups, based on their placement test scores. The experimental group was taught using concept-based instruction (CBI), while the control group was taught using a deductive approach. A post-test was used to measure the participants’ grammar performance after the teaching of both approaches, while a students’ engagement observation checklist and a satisfaction questionnaire were used for observing their learning engagement and levels of satisfaction with CBI, respectively. Based on the results of the post-test, no significant difference in the student teachers’ grammar scores was found. The results of the observation checklist indicated that there was a high level of learning engagement in the experimental group in terms of ‘Initiative’ and ‘Effort’ composition scales, while the ‘Disruptive’ and ‘Inattentive’ scales were low. Analysis of the satisfaction questionnaire indicated that the experimental group was ‘satisfied’ with CBI. They expressed that CBI could help them improve their grammar ability and provide them with confidence in learning grammar despite the difficulty with the language of instruction and the need for cooperation among peers. Based on these findings, some pedagogical implications and recommendations for further study were discussed.

Keywords: Concept-based instruction; deductive approach; teaching English grammar; student teachers; Cambodia

Introduction

Grammar instruction has a long history in the field of language teaching and learning. At the level of learning institution, teaching grammar is considered as the most difficult skill to teach (Baron, 1982; Brindley, 1984) and the most boring skill to learn (Abdu & Nagaratnam, 2011; Leki, 1995; Schulz, 2001). In general, both teachers and students appreciate the value of grammar lessons but they feel unease toward them (Jean & Simard, 2011; Kern, 1995; Loewen et al., 2009; Schulz, 1996; Siebert, 2003). Throughout the history of language teaching, language teaching approaches have been unceasingly changed to ensure the betterment of learners’ outcomes. These included Grammar Translation Method (1800-1900), Direct Methods (1890-1930), Audio Lingual Methods (1950-1970), Cognitive Approach (1970), Deductive Approach, Inductive Approach, and Eclectic Approach (1990s) (Kumar, 2013). Educators today seem to be faced with a choice: continue teaching centuries-old ways of teaching or throw them out in favor of innovation and creativity in order to move into a 21st century paradigm for teaching and learning (Kao, 2019).

According to the EF English Proficiency Index, Cambodia was ranked 97th among 112 countries in the world and 21st among 24 countries in Asia in terms of English proficiency level, while being grouped in the ‘very low proficiency’ category since 2014 (EF English Proficiency Index, 2021). Based on an online pilot survey conducted at the beginning of this study on eight English lecturers and 75 primary student teachers who finished an English grammar course at Battambang Teacher Education College (BTEC), most participants (75% of lecturers and 80% of student teachers) preferred to teach or learn grammar using a deductive approach. In a deductive approach, teachers first present grammar rules then highlight the examples of grammatical structures. Finally, students use the rules in order to produce examples. The expected outcome is to teach students to remember the grammar rules (Shrum, 2015; Thornbury, 2008).

Obeidat and Alomari (2020) pointed out that in a deductive classroom, the teacher teaches the lesson by introducing and explaining a concept to the students and then asks them to complete exercises and/or tasks to practice the concept. Deductive instruction teaches the grammar rules and use to students; it does not enhance their communication abilities. Moreover, a deductive approach teaches grammar in an explicit way to help students understand the grammar rules (Shrum, 2015; Thornbury, 2008). This approach has some disadvantages. For example, some students may find it difficult to understand when the class begins with a grammar presentation. They might not speak the appropriate language, the language that is used to discuss grammar rules. They also might not be able to comprehend the relevant grammar rules. Moreover, grammar explanation promotes a teacher-centered, transmission-style classroom where teachers’ explanation frequently precedes the participation and interaction of the students (Abdukarimova & Zubaydova, 2021).

A number of teaching approaches used as alternatives to deductive teaching have been proposed. One example is concept-based teaching and learning which has its roots in the early work of Taba (1966) who suggested that in order for teachers to teach students effectively they must have a working grasp of two levels of knowledge: facts and principles. Erickson and Lanning (2013) noted that since Taba’s work, the concept-based teaching and learning approach has had an impact on research, curriculum design, and teaching methods, in addition to influencing current discussions about the place of factual information in curricula today.

Concept-based teaching and learning is better known as concept-based instruction (CBI) — a method of curriculum design that emphasizes ‘a big concept’ or themes that cut across numerous subject areas or disciplines as opposed to subject-specific information (Erickson & Lanning, 2013). It has been known for its key features in encouraging students’ critical thinking or synergistic thinking, which goes beyond factual knowledge. It creates a link between knowledge and comprehension at the factual and conceptual levels (Erickson & Lanning, 2013). By asking different kinds of questions, teachers can boost the learning activities of the students and elicit their responses. CBI goes beyond teaching students to recall, know, and use skills (Erickson & Lanning, 2013). As Khiev and Khuon (2021) pointed out, several aspects allowed students to accumulate their engagements through CBI. First, students changed their learning styles in which the information went in one ear and out the other. Second, they could obtain rich and reliable information from various sources. Third, they could develop their critical thinking skills, problem solving skills, and other important skills. Next, they could foster their scientific thinking skills by using concepts. After that, they could become independent learners in their learning process. They could also advance their creativity and inquiry skills (Khiev & Khuon, 2021).

Empirical evidence has indicated that employing a concept-based approach in teaching grammar could yield promising results (Harun et al., 2017; Hill, 2007). For instance, Harun et al. (2017) claimed that CBI could potentially help improve second language learners’ grammar knowledge and use of language for communication because it facilitated their in-depth understanding of the structural forms and semantic meaning of the target language. CBI could also help initiate cognitive schemata of learners, enabling them to express the conceptual nature of grammatical forms (Hill, 2007). Moreover, through CBI and curriculum, teachers could help students build connections between the concepts they learned at school with their real-world activities (Giddens & Brady, 2007; Ignatavicius, 2017).

The need to explore the usefulness and effectiveness of CBI has received increasing attention across a number of disciplines in recent years, as indicated by the body of literature discussed earlier. In terms of teaching and learning grammar, however, as found in a pilot survey conducted by the first author at the beginning of this study, many teachers and students still prefer deductive teaching over the other approaches with or without realizing its drawbacks. Many studies have investigated the effectiveness of using either CBI or a deductive approach in teaching grammar (i.e. Abdukarimova & Zubaydova, 2021; Giddens & Brady, 2007; Harun et al., 2017; Hill, 2007; Ignatavicius, 2017; Shirav & Nagai, 2022), yet most of these studies investigated each teaching approach separately and were conducted outside Cambodia, the context of the current study.

Since there are few studies observing the use of the two teaching approaches in comparison to one another in a single study, and there is a lack of empirical research about CBI implementation in Cambodia, the current comparative study is necessary and timely. The findings of this study could potentially help teachers decide on a more effective approach in teaching grammar, thus using it to improve their students’ learning more efficiently and could possibly fulfill the current contextual knowledge gap.

Research objectives

This study aims to compare the use of CBI and a deductive approach in teaching grammar. It seeks to achieve three objectives as follows:

- To compare post-test scores between the control and experimental groups after learning with concept-based instruction and deductive approach.

- To observe the experimental group’s learning engagement in concept-based instruction.

- To examine the experimental group’s satisfaction with concept-based instruction.

Research questions

This study has three research questions:

Literature review

What is concept-based instruction?

The history of CBI in education is respectable. Taba (1966) suggested that in order for teachers to teach students effectively, they must comprehend several knowledge levels, ranging from basic facts to underlying concepts and principles. CBI is an approach to curriculum that moves away from subject-specific content and instead accentuates ‘a big idea’ or themes across multiple subject areas or disciplines (Erickson et al., 2017). CBI is a little different from inquiry-based learning, which is defined by many researchers as a teaching method that bridges the gap between the curiosity of the students with the scientific proven methods to exceed students’ critical thinking skills. By encouraging students to think more deeply and comprehensively, CBI can assist them in acquiring the necessary skills for living in the 21st century. The concept-based methodology aids students in understanding, doing, and knowing things. Erickson and Lanning (2013) noted that the development of students’ critical thinking and synergistic thinking, which goes beyond factual information but connects the factual and conceptual levels of knowledge and comprehension, has been greatly aided by concept-based curriculum and instruction. They explained that the purpose of asking different kinds of questions is to boost the learning activities of the students and to elicit their responses. In this manner, CBI is seen as a type of inquiry-based education that goes beyond recall, knowledge, and competence, but provides the way to attain knowledge and understanding (Erickson & Lanning, 2013).

Goals and stages of concept-based instruction

According to Erickson and Lanning (2013), CBI utilizes knowledge on two levels, the lower level (factual) and the higher level (conceptual) to establish structure in the brain for sorting, organizing, and patterning incoming information (concepts). Students are able to transfer their understanding, recognize patterns and connections at the conceptual level, and think more synergistically. Additionally, it increases intellectual sophistication by challenging teachers and students to think. The purpose of CBI is to combine students’ conceptual and transferrable levels of learning with their thinking, which will boost motivation, information retention, and deeper levels of comprehension (Erickson & Lanning, 2013).

There are two models of CBI (Chong (2019); Erickson and Lanning (2013). The present study used the concept-based model of Chong’s (2019), which prescribes three instructional stages. Stage 1 involves the identification of desired results including ‘big idea’ (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005, p. 276), concept, learning goal, essential questions, knowledge, and skills. In Stage 2, teachers determine acceptable evidence used to assess students’ learning outcomes in comparison to the desired results set in Stage 1. The evidence may be obtained through the use of various kinds of assessment. Additionally, the performance task which is a demonstration of knowledge and skills to a problem or task that is found in the real world is employed. In Stage 3, the learning activities are designed to go along with each unit, and it is utilized to design lesson plans that are implied from Stages 1 and 2. More importantly, it is built to take into account the outcomes from Stages 1 and 2 (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005).

Deductive approach

A deductive approach to teaching is defined as unceasing presentation of rules, generalizations, principles, or examples of the rules as they are applied in specific instances (Thomas, 1970; Thornbury, 2008). This approach has been widely used in many countries, and students with diverse backgrounds are familiar with this type of teaching (Widodo, 2006). According to Widodo (2006), deductive teaching is considered to be a traditional, teacher-centered, focus-on-form instruction. The approach might be advantageous because it can save time, is easier to process, includes examples, can develop cognitive skills of adult learners, and help learners precisely know what to expect in the classroom. However, the negative effects seem to outweigh the positive as learners’ involvement and interaction noticeably decrease and they rely mostly on their memory (Widodo, 2006).

Research on concept-based instruction

Research on CBI has been the center of interest of many researchers and teachers around the world. There have been numerous claims and empirical evidence about the success of using CBI in teaching grammar. Hill (2007), for example, suggested that CBI could be beneficial for language learners in a number of ways. First, a conceptual explanation for a grammatical form could help to enhance cognitive schemata among students. Second, applying CBI could make any error in students’ deductive thought processes more apparent to the teacher. After that, if the students overgeneralize a form as a result of instruction, the teacher may use error correction in the form of a recast to highlight the correct context of usage for the form (Hill, 2007). CBI could also enhance students’ understanding of the target language through discovering significant meaning-making language activities, and using the language as a tool to communicate (Harun et al., 2017). In addition, CBI could help build students’ understanding of the English passive voice, raise their awareness of the concept of a linguistic elements, enhance their phrasal and sentential meaning-making skills (Ahmed & Lenchuk, 2020), improve their ability to properly internalize and externalize their comprehension of the majority of phrasal verb meanings (Lee, 2012), improve their ability to comprehend different intentions and attitudes conveyed by sarcasm users (Kim, 2013), and improve their academic engagement (Romey, 2021). A computer-based conceptual approach to teaching English grammar was also proved effective in enhancing students’ recognition of grammatical voices (Lyddon, 2012).

Although previous studies reviewed above have discovered the effectiveness of using CBI in teaching English, especially in teaching grammar, it should also be noticed that these studies have been conducted outside of Cambodia; none of these studies have discussed the use of CBI in the Cambodian context. Moreover, most of these studies have investigated the utilization of either CBI or a deductive approach separately. To the best of our knowledge, no study has investigated the two teaching approaches in comparison to one another in a single study.

To date, the only pieces of written work concerning the implementation of CBI in Cambodian classrooms are those by Khiev and Khuon (2021) and Meng (2021). Khiev and Khuon (2021) proposed some potential benefits of implementing CBI such as helping to shape new learning styles for students, giving them rich sources of information, and possibly strengthening a number of skills such as problem-solving and creative thinking skills. Meng (2021) suggested that CBI could be piloted at New Generation Schools because these schools have virtually all the necessary resources for the implementation of the approach. As CBI has not been officially implemented, nor have its effectiveness or benefits been comprehensively and empirically investigated in Cambodian classrooms, it is necessary and timely to conduct the current study so that its findings can be used to potentially fill the current contextual gap of knowledge. It can also help teachers decide on a more effective approach in teaching grammar.

Methodology

Research design

The matched control experimental design (Kumar, 2018) was used in this study that aims to demonstrate the significant change of students’ learning outcome after applying CBI as compared to the deductive approach. In the matched control experimental design, according to Kumar (2018), pairs of participants are equally distributed into groups based on specific characteristics or variables which are almost identical such as age and socioeconomic status. In this study, pairs of the participants were distributed into the control and experimental groups based on their scores on a placement test. The control group was then taught with a deductive approach, while the experimental group with CBI. The content of the lessons covered past simple and past perfect simple, with each group being taught for two 90-minute sessions equally.

Sample and sampling techniques

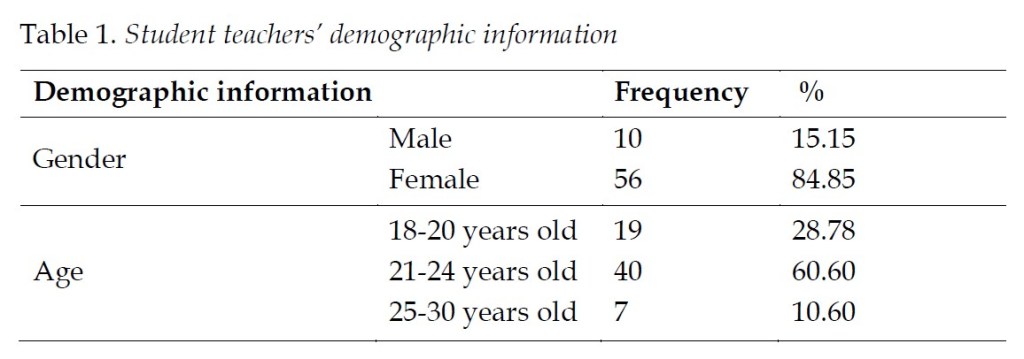

Seventy-five primary student teachers from three different classes who were studying in Year 1 at BTEC were asked to participate in the study. The participants had different levels of English knowledge and had never taken a selection test of English proficiency before entering the teacher education program of BTEC. Their experiences of writing, reading, vocabulary, and grammar were unreported to fit the course prerequisite. All participants were asked to take a placement test adapted from Lim (n.d). However, only 66 of them (56 females) were able to participate in both the placement test and the post-test. Based on the results of the placement test, two matched groups, control and experimental, were generated. In each group, there were 33 student teachers, 28 females each. The mean scores on the placement test of the two groups were equal, illustrating that the English grammar ability of the student teachers was equal prior to the experiment. Table 1 shows the student teachers’ demographic information in terms of gender and age.

Research instruments

- Grammar test: Test items for both the placement and the post-test were adapted from Challenging English 4-in-1 of (Lim, n.d). There were 25 multiple-choice questions, each having a stem and three distractors to choose from. The test focused on past simple and past perfect simple, which were covered during the experiment and took about one hour to complete. The post-test was administered after the two 90-minute sessions of teaching in both groups.

- Students’ engagement observation checklist: The checklistwas adapted from Cassar and Jang (2010) and was used to measure the level of student teachers’ engagement in learning. In the checklist, there were 18 items divided into four categories. Items 1, 2, 6, 9, 12, 16, and 18 were used to find out how much ‘Effort’the student teachers put in their learning process. Items 10, 11, and 15 measured ‘Inattentive’ behavior. Items 4, 7, 8, and 14 were used to show the ‘Disruptive’ behavior of the student teachers. Items 3, 5, 13, and 17 were about ‘Initiative’ behavior. ‘Effort’ and ‘Initiative’ scales measured positive behavior, while ‘Inattentive’ and ‘Disruptive’ were about negative behavior.

- questionnaire: A satisfaction questionnaire was adapted from Huang (2016) and was provided to the experimental group at the end of the treatment. There were two parts of the questionnaire. Part 1 consisted of fifteen 5-point Likert scale items in which the student teachers rated the given statements from 1 to 5 where 1 expressed their strong disagreement and 5 expressed their strong agreement. Part 2 contained an open-ended question asking student teachers to provide their comments on their experience with CBI.

- Lesson plans: Two different sets of lesson plans were created for the teaching of both groups based on the two instructional approaches mentioned above. For content validity, these sets of lesson plans were checked and modified based on comments of three experienced English teacher educators at BTEC. The instructional procedures of the two approaches are shown in Table 2.

Data collection

At the beginning of the experiment, 75 student teachers from three different classes were asked to sit the placement test. However, as mentioned above, only 66 of them (56 females) were able to participate in both the placement test and the post-test. Using a matched control experimental design (Kumar, 2018), 33 pairs of student teachers’ were assigned to the two different groups (each had 28 females). The control group was later taught with the deductive approach, while the experimental group with CBI, each for two 90-minute sessions. The sessions were video-recorded for later observation using the students’ engagement observation checklist. At the end of the sessions, the post-test was administered to measure the participants’ grammar performance. Lastly, the experimental group was asked to fill out the satisfaction questionnaire.

Data analysis

Quantitative and qualitative data were collected and analyzed using the following methods:

- Quantitative analysis: Independent sample t-test was used to compare between placement test scores and between post-test scores of the control and experimental groups. Moreover, frequency and mean scores were used for analyzing the number of responses and average in data derived from student teachers’ satisfaction questionnaires and the observation checklist.

- Qualitative analysis: Student teachers’ responses to an open-ended question in Part 2 of the satisfaction questionnaire were translated into English and analyzed qualitatively by following these steps: developing and applying codes; identifying themes, patterns, and relationships; and summarizing the data.

It is worth noting that quantitative data were analyzed in SPSS 21, while qualitative data were analyzed using Microsoft Word.

Results

This section presents the analysis of the scores from the post-test, the data from the student teachers’ satisfaction questionnaire, and the data from the observation checklist against each of the three research questions.

Research question 1: Is there any significant difference in post-test scores between control and experimental groups after learning with concept-based instruction and a deductive approach?

Table 3. The comparison of post-test scores between control and experimental groups

| Group | N | Mean | SD | Difference | t | p-value |

| Experimental | 33 | 18.091 | 5.828 | 1.788 | 1.159 | .251 |

| Control | 33 | 16.303 | 6.678 |

Table 3 presents the results of the comparison of the post-test scores between the control and experimental groups using independent-samples t-test. As seen in Table 3, in the post-test, the experimental group had the mean score of 18.091 (SD = 5.828), while the mean score of the control group was 16.303 (SD = 6.678). T-test results show that there was no statistically significant difference in terms of post-test scores between the experimental and control groups (t = 1.159, p>.05). This indicates that the student teachers in both groups had the same level of English grammar ability after the experiment.

Research question 2: What is the experimental group’s learning engagement in concept-based instruction?

Changes in the student teachers’ level of engagement in learning were examined using the data from the video observation. Four composition variables included ‘Efforts,’ ‘Initiative,’ ‘Disruptive,’ and ‘Inattentive’ behaviors of the experimental group.

Table 4. Results of the students’ engagement observation checklist

| Engagement scale | Observer 1 | Observer 2 | Mean |

| Effort | 4.28 | 4.35 | 4.31 |

| Initiative | 4.25 | 4.37 | 4.31 |

| Disruptive | 1.5 | 2 | 1.75 |

| Inattentive | 1.66 | 1.12 | 1.39 |

Table 4 shows the descriptive statistics using mean scores about four engagement variables. According to Table 4, the experimental group had higher mean scores for the ‘Effort’ scale (4.31) and ‘Initiative’ scale (4.31), and lower mean scores for the ‘Disruptive’ scale (1.75) and ‘Inattentive’ scale (1.39). This means that student teachers in the experimental group achieved higher scores in positive learning engagement behaviors and lower scores in negative learning engagement behaviors. This result indicates that student teachers in the experimental group had a high level of learning engagement.

Research question 3: To what extent is the experimental group satisfied with concept-based instruction?

Table 5. Student teachers’ satisfaction with concept-based instruction

| Statements | Mean | SD |

| Concept-based instruction helped me enjoy learning English. | 3.75 | .68 |

| I am more willing to speak English now. | 3.89 | .73 |

| Task activities gave me more opportunities to practice speaking English. | 3.91 | .86 |

| Using activities helped me remember more English grammar and vocabulary. | 3.72 | .80 |

| Using tasks gave me more chances for practicing grammar and communicating in English. | 3.78 | .67 |

| I enjoyed doing pair and group work. | 3.83 | 1.01 |

| I believe that I can learn English faster when I use concept-based instruction more often. | 3.54 | .80 |

| Task-based instruction provided a relaxed atmosphere. | 3.59 | .79 |

| Concept-based instruction fulfilled my needs and interests. | 3.35 | .85 |

| I am more motivated by the task that connects to real life situations than the activities in the book. | 3.89 | .65 |

| I have proved my communication skills through group discussion and result presentation. | 3.81 | .65 |

| I was willing to exchange ideas with my classmates in the group discussion. | 3.86 | .97 |

| Content-based instruction was more interesting than any other approach I ever experienced. | 3.59 | .92 |

| I could get a sense of improvement in my English-speaking skills after studying with content-based instruction. | 3.67 | .81 |

| I wish my teacher used content-based instruction more often in the future. | 3.91 | .86 |

| Total Mean | 3.74 | 0.80 |

Table 5 illustrates the results from Part 1 of the student teachers’ satisfaction questionnaire, which contained fifteen 5-point Likert scale items. The total mean of all the items is 3.74 (SD = .80), implying that student teachers in the experimental group were “satisfied” with the CBI classroom. Item 9 “Concept-based instruction fulfilled my needs and interests” had the lowest mean of 3.35 (SD = .85). However, Item 3 “Task activities gave me more opportunities to practice speaking English.” and Item 15 “I wish my teacher used concept-based instruction more often in the future.” had the highest mean of 3.91 (SD = .86). The student teachers’ satisfaction level ranged from being “uncertain” to “satisfied”.

The purpose of the last part of the satisfaction questionnaire was to elicit the student teachers’ suggestions or opinions about their experience with the CBI classroom during the experiment. As shown in Table 6, through qualitative analysis, the student teachers’ responses were divided into four categories: language improvement, confidence, language of instruction, and cooperation. The first two categories reflected the participants’ positive comments about CBI while the remaining two reflected their negative comments or their complaints about CBI.

Table 6. Student teachers’ suggestions or opinions about CBI

| Theme | Key concept and supporting quotes |

| Language improvement | Key concepts Students mentioned the improvement in their language skills after CBI such as improving communication skills and cooperation skills. |

| Supporting quotes Teaching using CBI can increase learners’ communication and gain more understanding about the lesson [S32]* [CBI] could help me to gain knowledge through exploring and thinking critically during classroom activities [S10] | |

| Confidence | Key concepts The students had a sense of confidence after being taught with CBI and their motivation in speaking English had increased to a certain extent through pair work, group work, and whole class discussions. |

| Supporting quotes [CBI] increases learners’ cooperation. There is encouragement by their teacher and teammates, which builds up my confidence. I really like this approach because the teacher provides the best explanation and there is good communication between the teacher and students as well as between students and students. [S15] | |

| Language of instruction | Key concept There was a mixed ability of students in each class which was the main impediment for some students, preventing them from acquiring the language well. English language is used as a medium of instruction; therefore, some students could not catch up well and they requested to use their native language (i.e., Khmer language) during the instruction. |

| Supporting quotes I want my teacher to speak Khmer because some sentences I could not understand and cannot translate them. [S37] I wish the teacher had given clearer instructions so that the students could understand better. [S9] | |

| Cooperation | Key concept Group work has been assigned during CBI. Though most students were satisfied with this task, some requested more time and encouraged those passive students to share ideas during the discussion. |

| Supporting quotes I want to have active cooperation between the teacher and students. [S22] I would like to see in the next class that there should be more time given during group discussion… [S3] There should be better cooperation in group work. [S4] |

* S32 refers to student teacher #32.

Discussion

The results of the present study showed that there was no significant difference between the student teachers’ grammar ability after being taught with CBI or a deductive approach. This indicates that teaching grammar using CBI may not be more effective than using a deductive approach. The findings of this study are contrary to those of the previous studies discussed above, for example, Lee (2012), Ahmed and Lenchuk (2020), and Kim (2013), which found a significant improvement in students’ grammar ability after being exposed to CBI. The insignificant difference in the student teachers’ grammar ability in this study is due in part to the duration of the experiment. Since the sample was selected from three different classes and some of them were found positive of COVID-19, there were a number of delays and issues related to getting an approval from the BTEC academic office. The three-session teaching periods had been reduced to two-session periods for both controlled and experimental groups, which must have critically affected the results of the post-test.

Student teachers in the experimental group showed a high level of engagement, while scoring higher on the ‘Effort’ and ‘Initiative’ scales and lower on the ‘Disruptive’ and ‘Inattentive’ scales. This is probably because CBI provided students with an engaging and interesting atmosphere, which might have maximized their positive engagement behaviors (Effort and Initiative) and minimized unwanted behaviors (Disruptive and Inattentive), compared to the deductive approach. According to Erickson and Lanning (2013), concept-based curriculum and CBI contributed to the required framework of learning, providing opportunities for students’ academic engagement and growth since they were aligned with the learning process and how the brain receives, processes, and stores new information. The present study’s findings are parallel with those of Romey (2021), who found that there was a strong correlation between concept-based curriculum and CBI and student academic engagement. This study’s findings are also aligned with those of Erickson et al. (2017), who demonstrated how lining up classroom instruction with a concept-based approach permitted students to engage meaningfully in the work, use higher-order thinking strategies and executive functioning skills, and increase ownership in their learning and academic engagement.

The quantitative analysis of the experimental group’s responses to the satisfaction questionnaire indicated that most student teachers in this group were ‘satisfied’ with CBI; their rating of the individual items ranged from being ‘uncertain to ‘satisfied’. The qualitative analysis also showed that their comments could be divided into four categories: language improvement, confidence, language of instruction, and cooperation. Since the student teachers were provided with opportunities to engage in pair work, group discussions, and individual presentations, they could build their confidence. Simultaneously, when the teacher educator applied various tasks during the teaching process, student teachers had a chance to communicate and express their opinions, which might have stimulated their motivation to actively participate in the learning process. This might also have created a relaxed and supportive learning atmosphere which was necessary for less confident student teachers to develop creativity and take risks.

Erickson et al. (2017) noted that critical thinking could not be developed in a learning environment where teacher-centered approaches were emphasized, such as lecturing, telling students how to think, or solving problems for them. Even though CBI offered various benefits, the student teachers also raised some complaints about CBI classes, namely the language of instruction and weak cooperation among their classmates. The student teachers in the experimental group were of mixed-ability, having varied levels of language ability, which prevented them from fully understanding the instructions provided in English rather than their mother tongue. This might have been the cause of the first complaint. Moreover, when group members did not understand the instruction clearly, they might not be able to participate well in group activities, which might have led to the second cause of the complaint, that is, poor group cooperation.

Conclusion and recommendations

This research has shown that there was no significant difference between the use of concept-based instruction and a deductive approach for teaching English grammar. However, the student teachers in the experimental group showed a high level of learning engagement and satisfaction with CBI. Although complaining about the difficulty in the language of instruction and lack of cooperation among group members during group discussions, the student teachers in the experimental group believed that CBI could help them improve their grammar ability and confidence.

Although this study found no significant difference in grammar ability between the controlled and experimental groups, it is recommended that teacher educators should employ CBI in their classes more often because it could help improve their students’ learning engagement, confidence, and satisfaction. However, teacher educators should provide clear instructions during tasks, especially by balancing between the use of English as a medium of instruction and the use of mother tongue for better understanding, as well as giving students an appropriate amount of time to complete each task.

Limitations and suggestions for further research

The limitations of this study are related to the duration of the experiment. Since the sample was selected from three different classes and some of them were found positive of COVID-19, there were some delays and issues connected to getting an approval for conducting the study. As a result, the three-session experiment had been reduced to two sessions for both controlled and experimental groups, possibly affecting the results of the post-test. Also, because of the limited duration of the teaching and COVID-19 restrictions, the student teachers’ performance in other aspects, such as critical thinking skills and speaking skills, was not measured.

Considering these limitations, future research should be conducted to measure student teachers’ performance in terms of critical thinking skills or English-speaking skills as a result of CBI application. Moreover, researchers who wish to replicate the current study should conduct their research over a longer period of time to find out whether or not time is a major contributor to student teachers’ performance in grammar or other language skills.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the editors and anonymous reviewers of the Cambodian Journal of Educational Research for the editorial support and helpful comments on an earlier version of this article. The authors would also like to thank Battambang Teacher Education College for approving and supporting the study and the student teachers for their participation.

Conflict of interest

None.

The authors

Sophon Hieng is a Vice-dean of the Faculty of Social Science Education at Battambang Teacher Education College, Battambang, Cambodia. He holds a Master of Education in TESOL and has more than 17 years of experience in teaching English at general and higher education levels. His research interests are in TESOL, Education, and Leadership.

Sondom Thlang is a Vice-dean of the Faculty of Social Science Education at Battambang Teacher Education College, Battambang, Cambodia. He holds a Master of Economics and a Master of Education in TESOL. His research interests are in TESOL and Economics.

Seanghai Nget is a Lecturer at Battambang Teacher Education College, Battambang, Cambodia. He holds a Master of Education in Educational Research and Evaluation. His research interests are in TESOL, teacher education, and research engagement.

References

Abdu, A.-M., & Nagaratnam, R. P. (2011). Difficulties in teaching and learning grammar in an EFL context. International Journal of Instruction 4(2), 69-85. https://dergipark.org.tr/en/download/article-file/59766

Abdukarimova, N., & Zubaydova, N. (2021). Deductive and inductive approaches to teaching grammar. JournalNX – A Multidisciplinary Peer Reviewed Journal, 372-376. https://repo.journalnx.com/index.php/nx/article/view/2940

Ahmed, A., & Lenchuk, I. (2020). A developmental step in the right direction: The case for concept-based instruction in the Omani ESP classroom. Arab World English Journal (AWEJ) 11, 15-30. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1287486.pdf

Baron, J. (1982). Personality and intelligence. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Handbook of human intelligence (pp. 308-351). CUP Archive. https://books.google.com.kh/books?id=VG85AAAAIAAJ

Brindley, G. P. (1984). Needs analysis and objective setting in the adult migrant education program. Adult Migrant Education Service. https://books.google.com.kh/books?id=51y0AAAACAAJ

Cassar, A. G., & Jang, E. E. (2010). Investigating the effects of a game-based approach in teaching word recognition and spelling to students with reading disabilities and attention deficits. Australian Journal of Learning Difficulties, 15(2), 193-211. https://doi.org/10.1080/19404151003796516

Chong, E. (2019). Concept-based curriculum and instruction [PowerPoint slides]. National Institute of Education, Singapore.

EF English Proficiency Index. (2021). English proficiency index: Cambodia. Retrieved October 21, 2021 from https://www.ef.com/wwen/epi/regions/asia/cambodia/

Erickson, H. L., & Lanning, L. A. (2013). Transitioning to concept-based curriculum and instruction: How to bring content and process together. SAGE Publications. https://books.google.com.kh/books?id=r8ZmAgAAQBAJ

Erickson, H. L., Lanning, L. A., & French, R. (2017). Concept-based curriculum and instruction for the thinking classroom. SAGE Publications. https://books.google.com.kh/books?id=4_U8vgAACAAJ

Giddens, J. F., & Brady, D. P. (2007). Rescuing nursing education from content saturation: The case for a concept-based curriculum. Journal of Nursing Education, 46(2), 65-69. https://www.harapnuik.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Giddens-resuing-nursing-education.pdf

Harun, H., Abdullah, N., Syuhadaâ, N., Wahab, A., & Zainuddin, N. (2017). The use of metalanguage among second language learners to mediate L2 grammar learning. Malaysian Journal of Learning and Instruction, 14(2), 85-114. https://doi.org/10.32890/mjli2017.14.2.4

Hill, K. (2007). Concept-based grammar teaching: An academic responds to Azar. Teaching English as a Second or Foreign Language, 11(2), 1-10. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1064989.pdf

Huang, D. (2016). A study on the application of task-based language teaching method in a comprehensive English class in China. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 7(1), 118. https://doi.org/10.17507/jltr.0701.13

Ignatavicius, D. D. (2017). Teaching and learning in a concept-based nursing curriculum. Jones & Bartlett Learning. https://books.google.com.kh/books?id=37M0DwAAQBAJ

Jean, G., & Simard, D. (2011). Grammar teaching and learning in L2: Necessary, but boring? Foreign Language Annals, 44(3), 467-494. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-9720.2011.01143.x

Kao, S. (2019). Methodology in TESOL. Author.

Kern, R. G. (1995). Students’ and teachers’ beliefs about language learning. Foreign Language Annals, 28(1), 71-92. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-9720.1995.tb00770.x

Khiev, V., & Khuon, V. (2021). សិក្សាបញ្ញត្តិដើម្បីអភិវឌ្ឍគុណសម្បទាសតវត្សរ៍ទី២១ (Studying concept for developing 21st century skills). MoEYS Cambodia.

Kim, J. (2013). Developing conceptual understanding of sarcasm in a second language through concept-based instruction [Doctoral dissertation, The Pennsylvania State University]. https://etda.libraries.psu.edu/files/final_submissions/8734

Kumar, C. P. (2013). The eclectic method-theory and its application to the learning of English. International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, 3(6), 1-4. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=917b0abdcad5728c3414658c3286db45065af00c

Kumar, R. (2018). Research methodology: A step-by-step guide for beginners. Sage. https://books.google.com.kh/books?id=a3PwLukoFlMC

Lee, H. (2012). Concept-based approach to second language teaching and learning: Cognitive lingusitics-inspired instruction of English phrasal verbs [Doctoral dissertation, The Pennsylvania State University]. https://www.proquest.com/openview/362038decdf65c397821e68a47fac72a/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750

Leki, I. (1995). Coping strategies of ESL students in writing tasks across the curriculum. TESOL Quarterly 29(2), 235-260. https://doi.org/10.2307/3587624

Lim, P. (n.d). Challenging English 4-in-1. Educational Publishing House, Plc. Ltd. https://www.openschoolbag.com.sg/product/primary/challenging-english-4-in-1-4

Loewen, S., Li, S., Fei, F., Thompson, A., Nakatsukasa, K., Ahn, S., & Chen, X. (2009). Second language learners’ beliefs about grammar instruction and error correction. The Modern Language Journal, 93(1), 91-104. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2009.00830.x

Lyddon, P. A. (2012). An evaluation of an automated approach to concept-based grammar instruction. The EuroCALL Review, 20(1), 113-117. https://doi.org/10.4995/eurocall.2012.16200

Meng, H. T. (2021). Curriculum reform: Introduce the concept-based curriculum and instruction in Cambodia to improve students’ learning in 21st century Proceeding of Integrative Science Education Seminar, https://prosiding.iainponorogo.ac.id/index.php/pisces/article/view/111

Obeidat, M., & Alomari, M. d. A. (2020). The effect of inductive and deductive teaching on EFL undergraduates’ achievement in grammar at the Hashemite University in Jordan. International Journal of Higher Education, 9(2), 280-288. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v9n2p280

Romey, A. (2021). The influence of concept-based instruction on student academic engagement [Doctoral dissertation, University of New England]. https://dune.une.edu/theses/377/

Schulz, M. (2001). The uncertain relevance of newness: Organizational learning and knowledge flows. Academy of Management Journal, 44(4), 661-681. https://journals.aom.org/doi/full/10.5465/306940

Schulz, R. A. (1996). Focus on form in the foreign language classroom: Students’ and teachers’ views on error correction and the role of grammar. Foreign Language Annals, 29(3), 343-364. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-9720.1996.tb01247.x

Shaffer, C. (1989). A comparison of inductive and deductive approaches to teaching foreign languages. The Modern Language Journal, 73(4), 395-403. https://doi.org/10.2307/326874

Shirav, A., & Nagai, E. (2022). The effects of deductive and inductive grammar instructions in communicative teaching. English Language Teaching, 15(6), 102-123. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v15n6p102

Shrum, J. L. (2015). Teacher’s handbook, contextualized language instruction. Cengage Learning. https://books.google.com.kh/books?id=DfBczgEACAAJ

Siebert, L. L. (2003). Student and teacher beliefs about language learning. Ortesol Journal, 21, 7-39. https://www.proquest.com/openview/abb641481839f979568ef4bc41e3e710/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=2038721

Taba, H. (1966). Teaching strategies and cognitive functioning in elementary school children. ERIC. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED025448.pdf

Thomas, E. W. (1970). A comparison of inductive and deductive teaching methods in college freshman remedial English. University of Pennsylvania. https://www.proquest.com/openview/9fb3cfbca59e49faf1a724fe48136c63/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y

Thornbury, S. (2008). How to teach grammar (Vol. 3). Pearson Education. https://books.google.com.kh/books?id=e9-OzQEACAAJ

Widodo, H. (2006). Approaches and procedures for teaching grammar. English teaching, 5(1), 121. http://education.waikato.ac.nz/research/files/etpc/2006v5n1nar1.pdf

Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by design. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. https://books.google.com.kh/books?id=N2EfKlyUN4QC